Anyone who has seen the gear page of this blog knows that I have a pretty good selection of gear that I can use on a daily basis. I have nice 35mm film cameras, very good medium format gear and even a lovely 4×5 camera. Ever since I added the Mamiya Universal to my arsenal there isn’t any medium format left that I can’t shoot. Except for 8×10, half frame and 127 film I have pretty much all formats decently covered and really don’t need any new cameras. Occasionally though there is a bit of unusual gear that tickles my fancy and the Sputnik Stereo camera was one of those examples. I didn’t exactly need it, but it was such an unusual camera that I couldn’t really resist?

Ever since I started reading about the history of photography I have been interested in stereo cameras. This kind of photography was actually hugely influential in the 19th century and was most popular after it was presented to Queen Victoria at the Great Exhibition in 1851. Since she apparently liked it, the technology became extremely popular until the financial crisis of 1873 made it too expensive for regular photographers to pursue and only large corporations still produced stereo images. Stereo viewers and images were still produced on a relatively large scale until the rise of colour television, but after the initial popularity waned they were usually seen as a gimmicky children’s toy rather than a “serious medium”. Nevertheless, many photographers in the 1850s and 60s were producing these images quite seriously and you can find many stereo images in the catalogs of some of the most eminent photographers of the era.

The thought of using a stereo camera myself intrigued me, but such cameras aren’t exactly common these days, because they weren’t a very mainstream photographic tool throughout most of the 20th century. There simply aren’t that many functioning cameras still around these days and most of them are very expensive. When I saw a picture of the Sputnik I just knew I had to get one for myself and of course Soviet cameras are always a good option when any first choice camera would be way too expensive. Soviet copies tend to be a bit cheaper than the alternatives, but of course they do have their own set of problems. I have a couple of Zorkis and a Lubitel already and they are riddled with issues. They are not very comfortable to use and have quite a few technical flaws that make them not the cameras that I usually grab these days. However, if you know what you’re getting yourself into, quality control issues and all, Soviet cameras can be a good option anyway. So, after a bit of back and forth I ordered a Sputnik in good condition directly from Russia and I was very excited to get to play with it.

The principle of stereo cameras is simple: Instead of the usual one picture per exposure, they take two pictures at the same time from slightly different angles. If you then look at these pictures through a stereoscopic viewer the picture will appear to you in 3D, which is really cool. Now we come to the main issue though: Of course these pictures are notoriously hard to share online, because we don’t have stereoscopic viewers integrated into our screens. Nevertheless I wanted to share the experience with you here on this blog and in my videos, so I started investigating.

The simplest way to share them is of course to just select one frame of the stereo pair and share it like with any other camera.

All pictures taken with: Sputnik | HP5+ | HC-110

© Lilly Schwartz 2020

© Lilly Schwartz 2020

© Lilly Schwartz 2020

© Lilly Schwartz 2020

© Lilly Schwartz 2020

© Lilly Schwartz 2020

Of course this kind of defeats the purpose of taking stereo images in the first place. If I just wanted to share normal 6×6 pictures I could just use my (very broken) Lubitel and get 12 images per roll instead of 6 stereoscopic images. In fact, comparing the two cameras it becomes obvious that they are very similar. The shutter feels largely the same, they both have bakelite bodies which means they are prone to reflections and light leaks, and they also break very easily because the bakelite becomes brittle over time. The only reason to go for a Sputnik instead of a Lubitel is to get the stereoscopic effect. Otherwise they are practically the same camera.

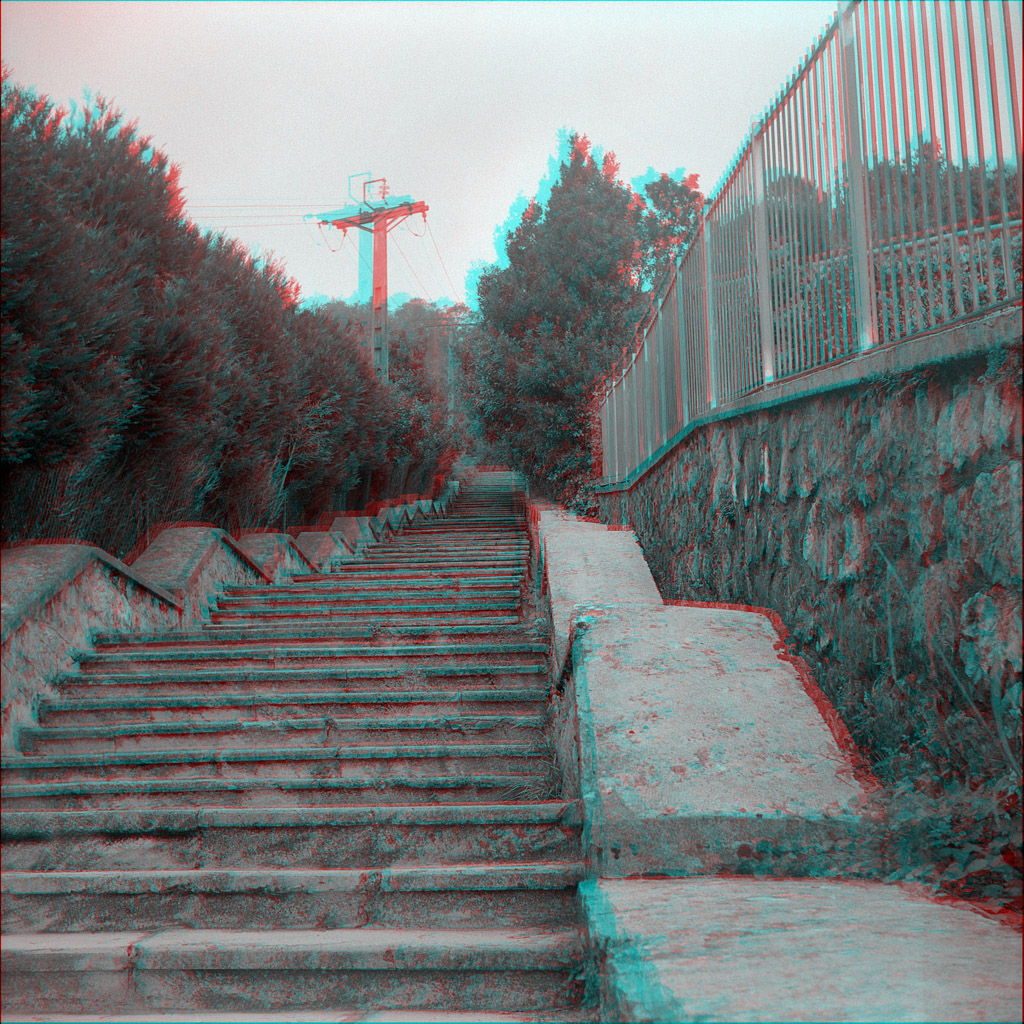

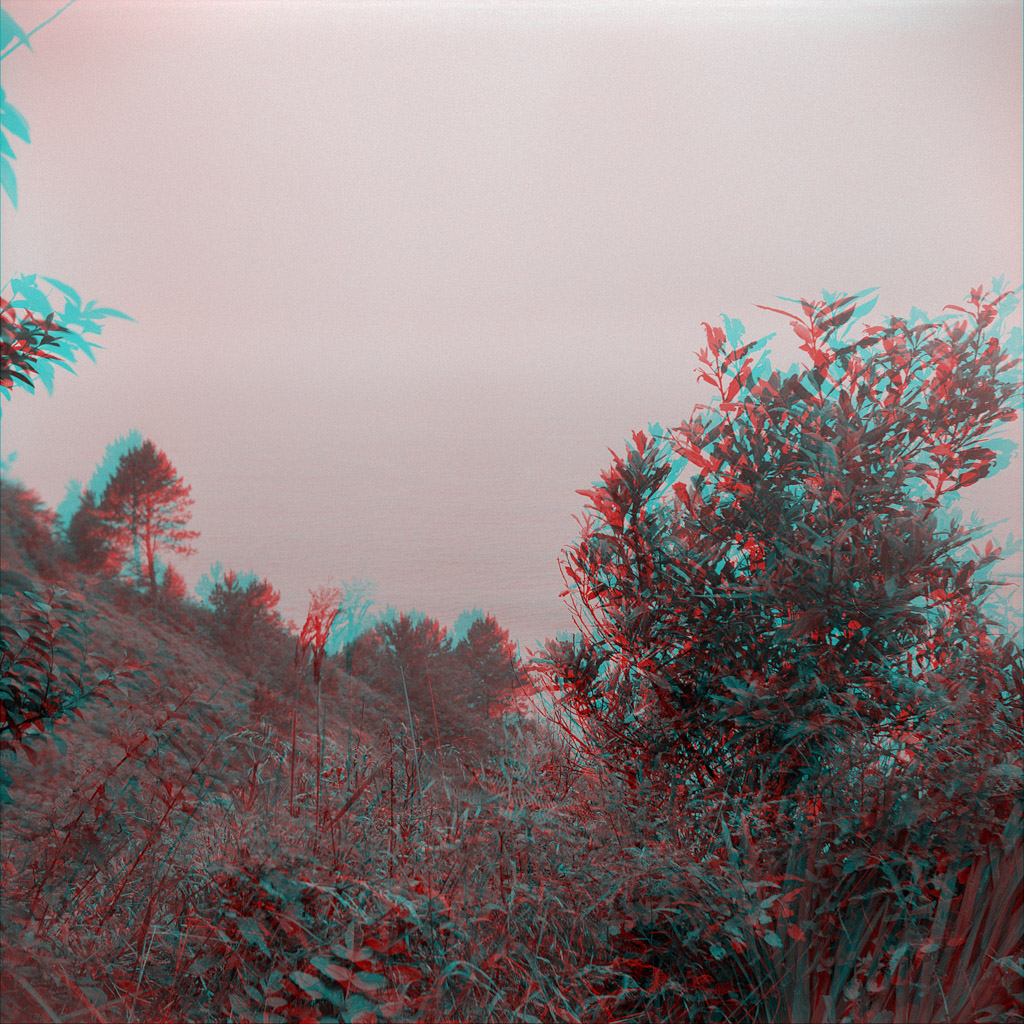

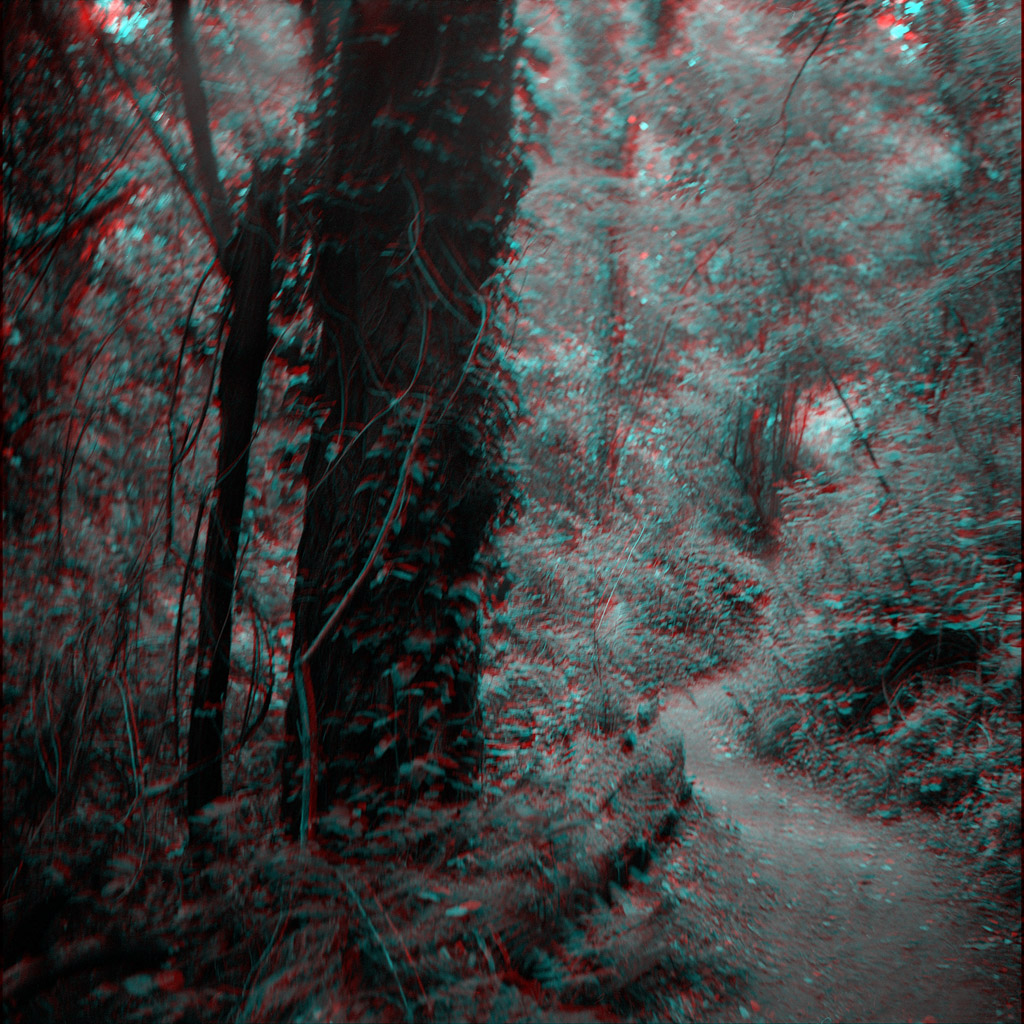

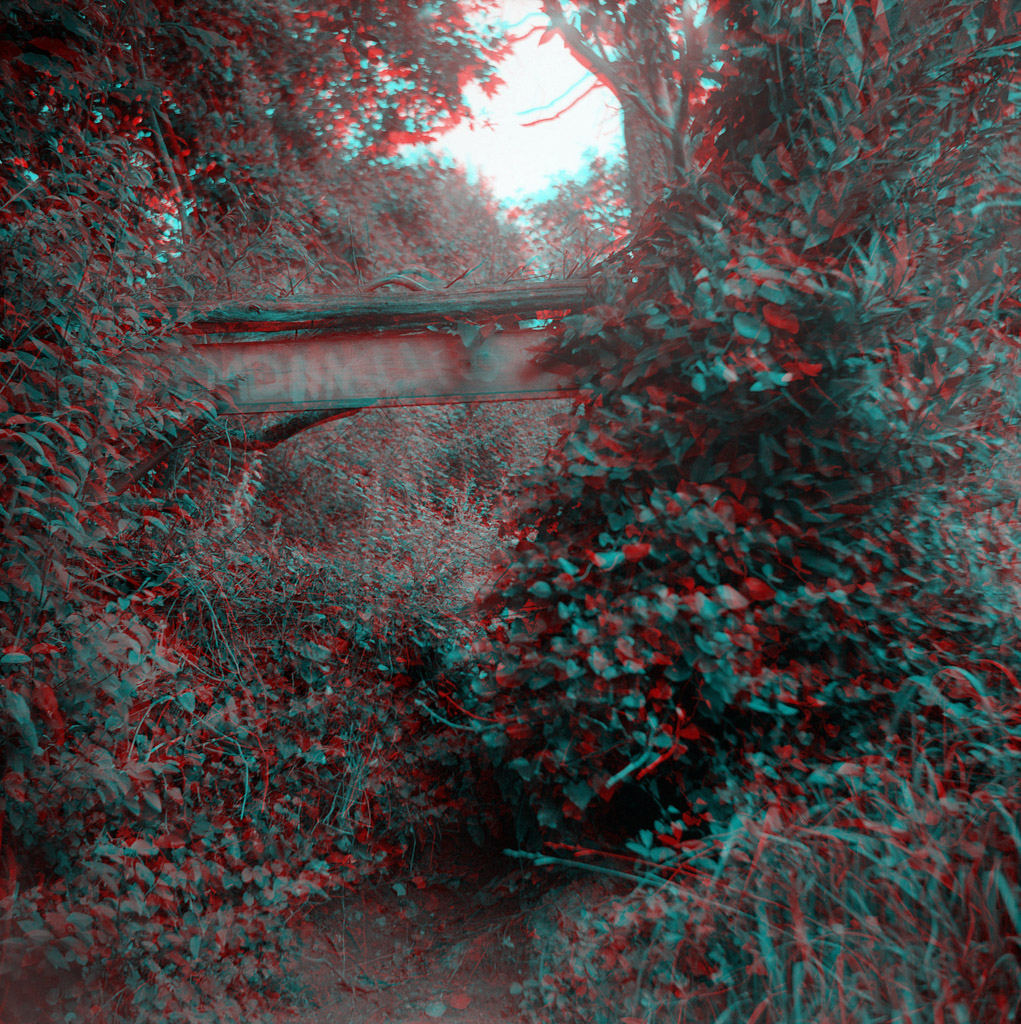

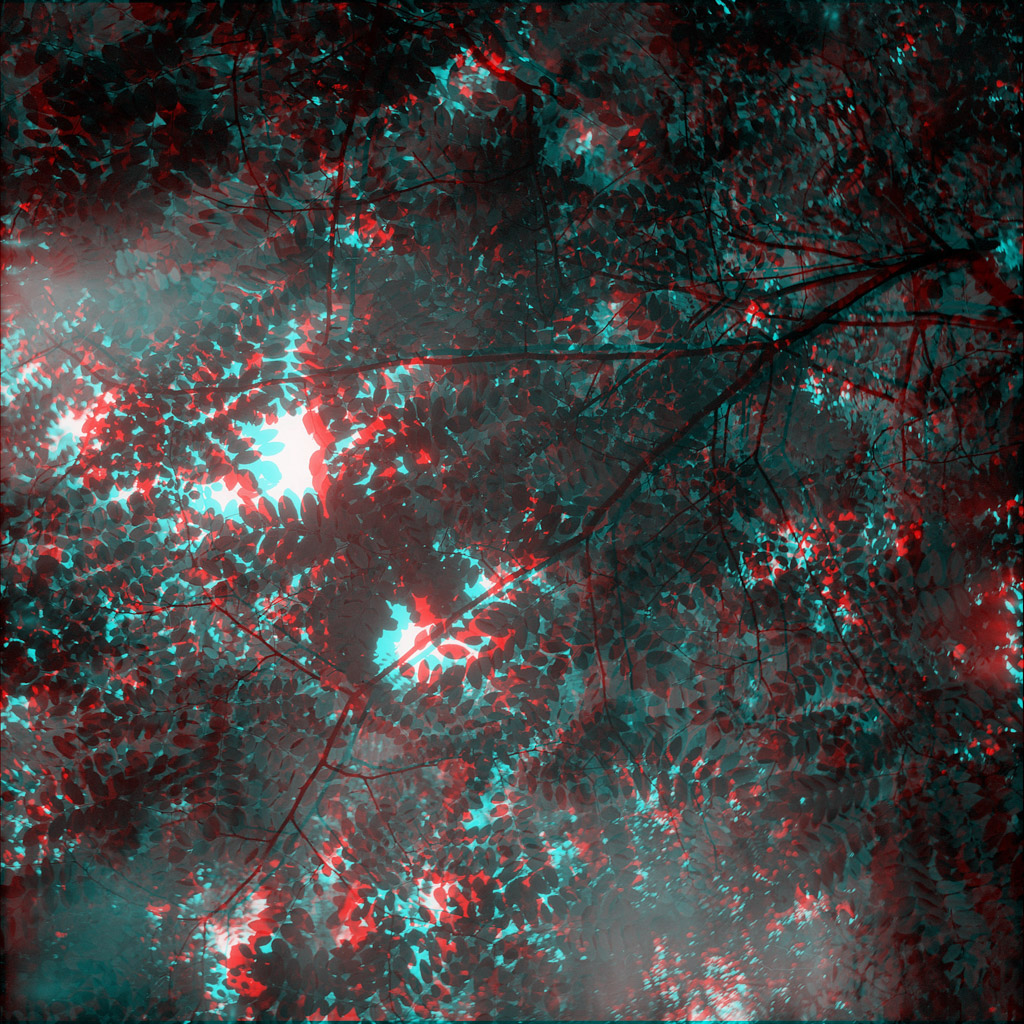

Another option is sharing the images as red blue anaglyphs.

© Lilly Schwartz 2020

© Lilly Schwartz 2020

© Lilly Schwartz 2020

© Lilly Schwartz 2020

© Lilly Schwartz 2020

© Lilly Schwartz 2020

The problem with this approach is however, that one needs special equipment to view these images, namely red blue 3D glasses and not everyone has them at home. Chances are that you won’t have any such glasses unless you have kids who managed not to break theirs yet. The other problem is that in comparison to the stereoscopic viewer this still feels like quite an unnatural way of looking at images which can give you quite a headache. In fact even stereo viewers are already prone to this unwanted side-effect, especially if you use them for a long time. Not ideal, but it’s already significantly closer to the experience you would have through the stereoscopic viewer.

The other option you have is to share the pictures as Facebook 3D photos. Here on this blog this means sharing them as little videos that I made on Facebook.

The process of taking pictures with such stereoscopic cameras of course also introduces additional challenges. The images really only work if there is a distinct foreground and background and this is quite a different experience from taking “flat” images where background foreground separation is mainly achieved through depth of field. This also means that taking one picture out of the context of a stereo pair will often have weak or weird composition which makes sharing just single pictures a futile exercise. Both anaglyphs and Facebook 3D images are much better at conveying what these pictures are actually like, but nothing quite comes close to the actual experience of looking at these pictures in the stereo viewer. Since the process employs depth perception in pretty much the same way that we see the world normally it is a much more immersive experience than looking at flat images or any technological approximations of this 3D process. I wish I could share this experience with you, but for now these approximations are the best we can do and if you ever get the chance to look at stereoscopic images in person, in the form of a children’s toy, in exhibitions or maybe in a library, I definitely encourage you to do so, since it is quite the unique experience.

This immersive experience is probably why these images were so popular during the dawn of photography since the viewership was still much less used to looking at flat photographic images as opposed to the way they normally saw the world. After all, we have to remember that the first photograph was printed in a newspaper only in 1848 and newspapers weren’t even illustrated at all until 1806! Photographs just weren’t as common as they are now when stereoscopic photos made a splash at the Great Exhibition. I can only imagine what it must have felt like to see such images from distant lands for the first time, in 3D, almost as if you were truly there!